Back to School Tech Tips: Obsidian and Knowledge Management System

- Brett Boelkens

- Aug 28, 2025

- 14 min read

Updated: Sep 13, 2025

This article is the fourth of four articles in regard to how to set up your new debate season and back-to-school experience for success. You can find part 1–3 at the links here, here, and here.

This particular article will focus on the issues with modern educational systems and information, and their impacts on your ability to learn at a high level, as well as how knowledge management systems like Obsidian can help solve those problems

Problems with Education

Teachers are usually truly dedicated to your learning, making themselves available for hundreds of (often unpaid) hours throughout the school year to be paid pitiful amounts compared to other educated professionals. I don’t disparage their work, but the education system is ill-designed for the production of highly knowledgeable people, which is difficult for you given that debate has high demands for deep cross-domain knowledge on topics.

People with more education-specific knowledge than myself have and will continue to discuss the issue, but our mass-production approach to education (one oriented towards the need to produce assembly line workers in the Industrial Revolution) is not conducive to you being well-prepared to do high-end debate research in regards to subjects like critical theory, economics, international relations, political philosophy, and morality.

We have a disaggregated and decentralized educational system, where the average high school senior will go through approximately six teachers during K-5th and forty-two teachers (six periods times seven years) from 6th-12th, for a total of ~50 distinct teachers through your primary education. Even if we assume all these teachers worked at the same institution like a K-12 school, allowing for easy cross-grade level coordination and communication, and this school had a unified education plan for a student for lesson plans from kindergarten to 12th grade, there will be gaps in your education. A common experience is your seventh grade math teacher being somewhat unaware of what your sixth grade math teacher taught you (even if both teachers taught at the same school). This doesn’t assume a class needing to address the needs of students who were taught with multiple curriculums (or multiple teachers’ interpretation of those curriculums) from different states or the multitude of students who clearly missed something or had other education issues when those prior year’s curriculums were taught.

Because of the fact there’s ~131,000 K-12 schools, all of which are obviously at different levels of quality and funding, and the fact its nigh near impossible for a teacher to predict what small minority of schools and teachers you encountered, most teachers are forced to adopt a “paint-by-numbers” approach. Despite goals of no child being left behind, some clearly are, and those who aren’t still might have major gaps in their knowledge that haven’t been addressed. This problem is exacerbated at a college level, where there’s even more variation in student’s knowledge bases and even higher demands for intellectual activity (as universities are usually near the cutting edge of what humanity knows).

Our education system is systematically incentivized to minimize your understanding of knowledge that is not easily proven by test score answers from standardized testing. Similarly, if you only understood a concept well enough to select the most-correct answer out of four letters, that is not a sufficient understanding to actually know the topic.

Both of these trends are important to acknowledge; the game has been rigged against you learning things at a level of people who truly know the content. You are much less likely to be a great thinker compared to those in the past given that your education was for the masses and not specific to you and your needs, unlike the student specific tutoring often undergone by great philosophers (see the link here). However, generally speaking, this is not a huge problem. Despite somewhat commonplace difficulties in subjects like math in primary school, it’s relatively easy enough to get by and learn it yourself (at least compared with high-level macroeconomics or criminal justice system analysis).

This cannot be said for subjects like debate, an activity often with minimal, all-encompassing education about debate strategy and topic areas. Unlike school districts’ curriculum guidelines, which seek to minimize the harms of decentralized education by increasing the similarities in how and when content is taught, debate coaches, judges, other debaters, and private tutors do not coordinate with each other, and many are at different stages in the process of learning debate and topic knowledge. Even at one of the most expensive debate camps in the country, there will be private debate coaches with 3/5 and 4/5 knowledge, even if they have a 5/5 skill in teaching (and vice versa), and if you count how many private debate coaches there are, there will be a similar number of distinct interpretations of debate strategy and ideal affs and negs. A three-time TOC winner won’t necessarily be the end-all be-all of everything there is to know about debate, and the same applies to every debate participant regardless of qualification. Someone will be well accustomed to strategies related to extreme impact turns, theory debating, or creative counterplans, but be very weak in coaching you about an anti-blackness kritik or Nietzsche kritik. And remember that very few of these debate coaches are knowledgeable about what you know (your known-knowns), what you know you don’t know (your known-unknowns), or what you don’t know that you don’t know (your unknown-unknowns).

All this means that you need to take personal responsibility for your own pedagogy and learning.

Problems with Too Much Information

On top of the decentralized knowledge source problem, debate requires you to be highly knowledgeable about generally applicable theories of behavior, power, and moral/critical philosophy. Take the current Sept-Oct plea bargaining topic; if running a coercion contention, I’d highly advise being able to answer questions related to unconstitutional conditions, duress/unfree contracts, power imbalances, info asymmetry, rights commodification, and consequences external to the deal. You should be able to give an example of what a contract free of coercion would be, and why plea bargaining does not meet those conditions. What specific features of plea bargaining are independent warrants for why it is coercive? Under theories of bargaining, can a contract be free if there is a monopoly on who you can contract with, if there are extreme consequences if you don’t sign, or if the other party “holds all the cards?” Similarly, does contract law apply to governments, specifically in the judicial process? Can any bargaining which the state can take away your rights or even your very life be considered free bargaining without a power imbalance or duress? Do I have a “right to choose not to have a right,” or otherwise say my “choice” to exercise my rights can be treated as a bargaining chip for me to get a more favorable deal? Does commodifying a right, once thought to be inalienable, as something that can be “bought” and “sold” transform that right into a privilege?

The coercion contention will be one of the go-to neg arguments, but to debate this argument on a higher-level and be more likely to break to out-rounds, you need to understand the core theory behind contract law and unconstitutional conditions in relation to coercion. You need to at least entertain these questions and think of what possible aff responses to these arguments would be.

This is only one contention, a relatively basic and stock one and that, but learning the core concepts makes all the difference between a good coercion debater and a bad one. Apply this general principle to every aff and neg contention on a topic, and multiply that by all topics you will ever debate. Assuming that each topic has three contentions for aff and three contentions on neg, and you debate every NSDA topic (five total, including NSDA Nationals) over the course of a four year high school debate career, you’ll need to be familiar with the underlying theory of 120 contentions if you want to win the TOC. To be thorough, add any generic arguments that you are likely to see in almost any debate, such as topicality, theory, and kritiks, and your responsibility to think critically becomes even bigger.

120+ is a big number. However, do not give up your hopes of winning big or quit debating because of your worries about fulfilling this huge obligation. Of course, not all debaters think on this level. Similar to the humorous principle in zombie movies that “you don’t need to be the fastest runner alive, you only need to be faster than the next guy,” you only need to be more knowledge about the core theoretic issues then whatever team you’re debating, and ultimately, the competition at that specific tournament.

What can we do to minimize this burden? Some debaters heavily specialize in a specific sub-type of argument, like literature surrounding one specific kritik, which is a viable option because of its ability to “up-layer” substance issues related to contentions (as it’s generally agreed that kritiks come before substance unless your opponent wins the framework debate).

Though this advice will also be useful to the kritik debaters, alternatively, jot down notes to increase your long-term retention of theories underlying the logics of specific contentions. I’ve often decried the recent NSDA habit of similar and repeated topics, but this pattern, as well as the similar underlying logics of contentions across multiple dissimilar topics, means that 120+ contentions does not mean 120+ theories to learn. Recall our earlier example on plea bargaining and coercion. The philosophy surrounding free contract law has a rich history, and is heavily intertwined with theories of social contracts and natural law, which is useful for topics related to our relationship with governments (such as the 2025 Nationals topic on the justness of violent revolutions or the 2024 Nationals topic on the right to secession). Similarly, free choice frameworks can implicate some contentions related to economics like with taxation (2024 Nov-Dec) or government involvement in markets (2022, 2023, and 2024 Sept-Oct). Free choice also alters the justness of government policies designed to alter the behavior of its citizens like with criminal rehabilitation (2024 Mar-Apr) or civil liberties during a public health emergency (2021 Nationals).

Most theories are also interconnected with each other, meaning your notes about contract law and coercion will be useful for other subjects, such as reference material for Marxist critiques of capitalism for its unfree contracts or how labor markets ought to function (and how they might be dysfunctional and coercive).

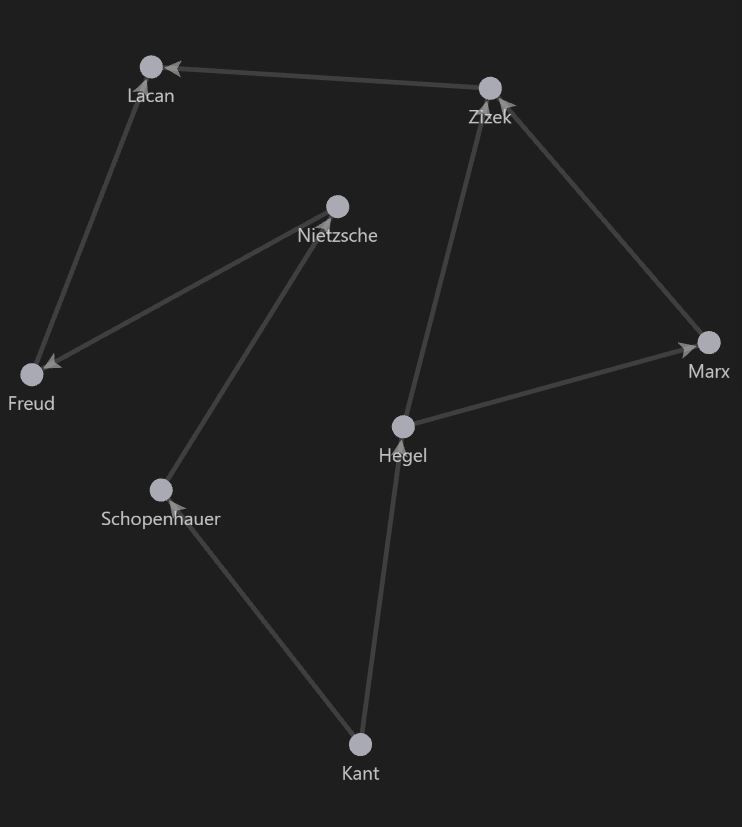

Similarly, most philosophers build on the work of prior philosophers, and knowing the intellectual heritage of an idea tells you BOTH why that current version of that theory might be more correct then prior theories AND how different philosophers of distinct disciplines interact with each other. For instance, take Kant, which caused an intellectual movement and two philosophers fundamental to the current views of a modern philosopher Žižek, who currently focuses on Marxist, Lacanian/Hegelian psychoanalysis. Kant inspired Schopenhauer, who wrote “The World as Will and Representation” which inspired Nietzsche with the will to power. Though not well-crediting Nietzsche, his ideas were very influential in the development of psychoanalysis by Freud, which eventually led to Lacan’s version of psychoanalysis. An inversion of Kant and his metaphysics led to Hegel, and Hegel’s metaphysical dialectical method was key to dialectical materialism under Marx. Fundamentally, this is a somewhat oversimplified three-pronged intellectual for Žižek. From Kant, we get (a) Schopenhauer -> Nietzsche -> Freud -> Lacan, (b) Hegel, and (c) Hegel -> Marx. All three form the modern thought of Žižek, which is fundamental to understand if you want to debate the psychoanalysis kritik at a higher level and cite Žižek.

I understand this sounds like a lot, and the interwovenness of intellectual history and the development of ideas from seemingly distinct authors is complicated, but there is technology called Obsidian that allows you to connect all your notes on each of these ideas and authors, and see the connections visually.

Knowledge Management Systems and Obsidian

Unlike math, which is one subject that is often taught somewhat sequentially in a rough order K-12, the knowledge utilized in debate involves virtually every subject area imaginable, is very self-taught, and is not well-organized in its teachings. It is nearly impossible to know everything there is to know for debate, as to some degree, debate involves knowledge of all things. On merely an impact level, you must be aware of the following:

Theories of hegemony, the liberal international order, and great power war.

Economic interdependence, trade, and motivations for diversionary and/or resource wars.

Security dilemmas, arms races, and alliances.

Biodiversity, climate change, and positive feedback loops.

Democracy, fascism, and populism.

These are just some big-ticket impacts; people make entire careers out of studying sub-portions of merely one of these areas of study. Worse still is the fact that these issues themselves are interconnected with each other, such as inequality causing populism that increases populism and the risk of conflict escalation due to nationalism, a weakened international order, as well as more climate change. That’s a lot to think about, especially when we haven’t even considered how we got to populism in the first place.

To the degree to which you need to know all things (at least on a level sufficient to win a debate on it), and to the degree all things are interconnected with all other things, it’s worthwhile to have a Knowledge Management System (KMS). This acronym is unrelated to the one commonly used in text, so please don’t tell your parents you’re interested in KMS.

Obsidian is one example of KMS. I will leave a detailed explanation of how to use Obsidian to people more experienced in the software, as I would personally say I am more so an expert on Obsidian Entertainment like with Fallout New Vegas and Outer Worlds as opposed to Obsidian the KMS.

Often when we write notes, particularly on paper in notebooks, these are self-contained documents, often with that note book being either entirely forgotten or occasionally perused after a class is done. They are not well designed for long-term retention across years of study, and they’re not great for cross-disciplinary studies. Like in our earlier example, your math notebook is for math, and when a new year or class comes along, you usually just get a new math notebook and put away the old one. Math does build on top of one another, and it’s good to keep old formulas and principles for future reference. However, you usually don’t worry about the potential interactions between the phenomena and philosophy of math and non-math subjects like you would with the liberal international order and other subjects related to it, such as theories of power in international relations, the rise of authoritarianism/populism, international finance/law, US hegemony/leadership, and the behavior of Russia and China.

Theory Behind Using Obsidian

This is why an interactive notebook with links connecting disparate subjects is useful, as the links show the interconnectivity of different subjects. Think of Wikipedia, where a summary of the entirety of human knowledge can be found, but the beauty of Wikipedia is that it shows the connections between key subjects through its hyperlinks (allowing the connection of very separated subjects like in Wikipedia Races). Though we don’t usually view these links visually, each article is a node connected to every other article that it links to (or other articles link to it). Visual showcases of these links are nutty, and can be found at the link here. On a much smaller scale, in-built in Obsidian is a visual representation of the linkages between your notes.

This can be on a small scale, such as connecting your class notes to a central node. The PSC 211 Comp Ptx is the hub for my Comparative Politics course. All my class notes go to the course hub, and then the course hub node is connected to my main UNLV hub node where all my classes are connected to. Something additional that is not shown here is the interconnectiveness of these nodes, such as connecting my general theory notes about developing/developed countries and (non)democratic regimes to their respective examples. If one of these chapters would be good reference material for another class or area of study, I would also link that chapter to that second hub node as needed.

Obsidian can also be used on a more macro-level, big-picture scale, connecting all major concepts and ideas to each other in a way that makes sense to you. The above pictures show all the notes or files that I have connected to my biopower node related to Foucault. I can see that Foucault led to follow-on theories by Mbembe, Deleuze, Agamben, and Han, and I have a literature node that connects to my notes on Foucault’s book “Discipline and Punish.” Some of these nodes are connected to nodes of their own, so if I selected my Deleuze node, that would show me all the links in the node (or links to that node). From this, I can see how Deleuze worked with Guattari to develop schizoanalysis, assemblage theory, and territorialization. These concepts can link me to authors that followed-on to the work from Deleuze and Guattari, such as Mark Fisher, Curtis Yarvin, and Nick Land. This also connects back to psychoanalysis with the work of Lacan and Žižek, which connects to Kant by working backwards through one of the author chains mentioned earlier.

This also works with debate lecture notes, such as connecting notes from your coach on a specific counterplan to your theory notes on conditionality or how to best extend counterplan arguments in the 2NR. You could also connect that counterplan node to that topic’s topic lecture or an RFD for a round where you debated that counterplan. The possibilities are endless.

With any one of these nodes, you can stop and look at your notes related to that author to better understand how that node connects to another node. It’s as detailed as you need it to be, and given the many, many topics available in debate, and the level of detail needed for each, it is something worthwhile investing time into as a notetaking tool.

If you want to use a sandbox example to play around with Obsidian before you download the software (for reference, it is free software), view their help page (linked here), and on the top right is an interactive visual representation of their hyperlinks within the online help menu.

Another method of organization is tags, which function like hashtags on social media as you can select any tag and then see all instances where there’s a note you’ve used that tag. This allows grouping similar concepts even if they are not directly linked. For instance, we could use a #Deleuze tag to indicate that either the author Deleuze was involved, or the concept was Deleuzean. To some degree our links to this, so this may render the tag unnecessary. You can also have a more top-level tag #psychoanalysis, which would connect Freud, Lacan, and Žižek (among others not listed), and you could include Deleuze or Foucault in here as well despite the fact they were critics of traditional psychoanalysis. Tags and links are both grouping/connection methods, so use either or both, but remember that only links allow visual representations.

This is fundamental for solving the decentralization problem—though you cannot change what content is being taught, you now have a searchable, organized repository of everything you have ever learned. If your teacher reteaches some trigonometry that a previous teacher already covered, you now have a hard visual connection showing that trigonometry was important for both classes and you’re more likely to remember the big picture of why trigonometry is important in both contexts. Slowing and iteratively adding these connections through your notes is valuable not only for ensuring info is not lost in old notebooks, but also for learning the concepts by showing their interconnectedness.

This is true even in situations where you did not consciously make that connection. For instance, mindlessly, through the process of you adding connective tissue via your smaller nodes, it can show grander connections between authors and intellectual history that you haven’t thought of before. Obviously, you are consciously making these one-to-one connections, but over time, you’ve built the technological notebook version of the “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon,” discovering larger connections you likely wouldn’t have naturally thought of yourself.

Strikingly, this is a very good method to discover potential contradictions in what you've learned. That conflict between different knowledge presents a new jumping off point for you to learn if there's something incomplete about your knowledge of the world, and the fact that these two facts are in fact reconcilable, or that some of your old knowledge was wrong and you were taught incorrectly. Seeing your old and new notes (or at least similar subject notes) side-by-side calls attention to the fact something is wrong, as opposed to a fuzzy feeling in the back of your head that this doesn't sound like what Mr. Lerma in 7th grade history taught. Maybe you were taught badly, perhaps intentionally to fulfill a political purpose (such as when thousands of children learn creationism or the potential joys of being a slave). Alternatively, it is possible you were taught differently with incomplete information given your age, which gives you new knowledge about your lived experience and allows better questions about why you were taught a specific way (something worthwhile considering especially for those interested in teaching).

I would recommend starting this process early in your life, particularly if you're very interested in political science, as finding a way to condense all the important knowledge you will every learn into a computer that can out-source much of your memory related tasks and discourages secondary re-readings to relearn information you once knew (but wrongfully thought you would remember). Our meatbag brains are inherently limited in what we can remember, and its better for you solve the problems from decentralized education via software then to hope somehow society will fix it before you're done with school. Hint: they're not.

Comments