How to Effectively Use Briefs

- karkingkankee

- Dec 26, 2025

- 16 min read

The intention of this article is to be a comprehensive guide to educate a debater, particularly a novice with little debate experience, on how to use a LD (Lincoln-Douglas) brief. This includes a cross-brief comparison of all major LD briefs on the market, with price point and size comparisons, as well as advice that should be broadly applicable to any brief you use.

After reading this article, even if you (sadly) do not prefer using Kankee Briefs, you should be well equipped to use any brief you have access to, and be informed on whether your team buying another brief would be worthwhile.

This article attempts to explain a relatively complex issue with the differences in file formatting comparison and how that impacts individual debaters; if you are an expereinced debater and/or coach, and want to add tips to this article, please email me at karkingkankee@gmail.com. There are many resources online; however, there are few resources that explain how to effectively utilize those resources.

Prerequisites/Background

Before reading further, I would highly recommend that you have a basic grasp of concepts related to debate files, such as how to cut a card and how to use Verbatim. Below are some links that explain the foundational concepts we will utilize in this article

Paperless Debate - Website Download for Verbatim

How to Cut a Card - Lawrence Zhou at VBI

Finding and Cutting Evidence [video tutorial] - Debate Guru

I would also have at least a minimum understanding of circuit debate terminology for the sake of knowing how the arguments presented in each brief function (see the debate jargon dictionary linked here.)

What Briefs Are Available?

Main LD Organizations

There are 5 primary brief organizations for LD; Kankee Briefs, Isegora Briefs, Victory Briefs Institute (VBI), Champion Briefs, and The Forensics Files (TFF).

Two are free (Kankee Briefs and Isegora Briefs) and three are paid (VBI, Champion Briefs, and TFF). VBI is $150 annually. Champion Briefs is $30/topic, or $175 annually. TFF is $35/topic or $130 annually.

Other LD Organizations

There are also two other debate organizations, both of whom offer paid briefs, called Debate US and Pocket Coach Academy (PCA).

These organizations were not active, or at least not popularly known about, when I was a debater. I have very limited knowledge about the quality of their files, and I would prefer not to spend the Kankee Briefs Patreon fund on reference material for briefs for this article. This is an overarching framing issue when buying briefs; it is hard to assess the quality of paid briefs before paying for access in order to assess their quality (at which point you usually cannot ask for a refund).

Hypothetically, Debate US and PCA could have briefs vastly superior to every file I have ever produced, and I should quit running Kankee Briefs in favor of them running the show. Alternatively, as another hypothetical, their files could also be of a lower quality than Kankee Briefs, or on par with what we produce. I simply do not know.

Because of that, as well as the fact that I believe DebateUS and PCA are not as established reputation-wise as VBI and Champion Briefs, I will provide reference info about the authors of these briefs as a substitute.

DebateUS

DebateUS files are $20/month, or $89 annually.

Director: Stefan Bauschard. Linked here is Bauschard’s Tabroom paradigm, linked here is Bauschard’s bio/resume on the DebateUS website, and linked here. is his Linkedin page. He also writes extensively on generative AI on his Substack, linked here.

For disclosure purposes, several years ago, I was in contact with Bauschard about a coaching position which unfortunately fell through. This does not implicate my assessment of DebateUS.

Pocket Coach Academy (PCA)

Additionally, there are several other organizations that periodically release files, but in what I believe in not in a consistent enough manner to rely on them for every topic. These include Classic Debate Camp (linked here), The Debate Intensive (TDI) (linked here), and the National Symposium for Debate (NSD) (linked here). For reference, I believe NSD briefs are now made by the people who previously made Premier Debate briefs.

This article is a working document, so if you believe that these other briefs ought to be included on the comparison table next to the others, please email me at karkingkankee@gmail.com.

Overview of Briefs

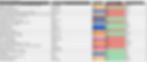

Cost | Free | Free | $89/year | $100/year | $130/year | $150/year | $175/year |

Topic Analysis? | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | Yes (1), Free Online | Unknown | Yes (1) | Yes (~4) | Yes (~4) |

Pre-Cut Cards | Yes | Partially | Yes | Partially | Partially | No | No |

Founding Date | 2019 | 2024 | 2015 | 2023 | 2004 | 1989 | 2012 |

Current Director | Unknown | ||||||

Approximate File Size | ~600-700 pages (Brief and AT File) | ~150 pages | Varies | Varies | ~100-150 pages | ~200-300 pages | ~600 pages |

Block Files Available | Yes | No | Unknown | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Other Files | NCFL | N/A | PF, Policy, UIL, speech | PF, Policy, UIL, speech | PF, Policy, UIL, Congress, Big Questions | PF | PF |

File Type | Word Docx/PDF | Word Docx/PDF | Word Docx | Word Docx | |||

Table of Contents | Nav Pane | Nav Pane and Table of Contents | Nav Pane | Nav Pane | Table of Contents | Table of Contents | Table of Contents |

How to Navigate a Brief

General Format

Briefs generally conform to the following formats:

Kankee Briefs: general topic analysis, contention-specific summaries, aff/neg contentions, with aff/neg blocks released later in the AT File.

Isegora Briefs: table of contents, general topic analysis, topicality cards, aff contentions, neg contentions

Debate US: online free topic analysis, paid aff contentions, paid neg contentions.

Pocket Coach Academy: paid aff contentions, paid neg contentions.

TFF: table of contents, topic analysis, definitions, aff case, neg case, aff extensions, neg extensions, aff blocks, neg blocks, rebuttal overviews

VBI: table of contents, 4x general topic analysis, general evidence, aff/neg contentions

Champion Briefs: table of contents, 4x general topic analysis, aff contentions (with a paired contention-specific summary), aff blocks, neg contentions (with a paired contention-specific summary), neg blocks

As a general rule, most briefs will have a general topic analysis at the top. Some briefs, like Kankee Briefs and Champion Briefs, have contention-specific topic summaries to explain the intricacies of the argument and potential strategic benefits/concerns.

Header Hierarchy and PDFs/Word Docx

Notice in the table above that there are some trends in PDF briefs when compared to Word Docx briefs. PDF briefs have the plain text of cards, usually not including any typical card formatting like underlining, highlighting, or emphasis. This is because the PDF file format is designed to minimize the formatting that can be copy-pasted from the file. Cutting a card for a brief to be released as a PDF is largely a waste of time due to the technical limitations of PDFs. In contrast, Word Docx briefs are usually partially or completely pre-cut the cards, so you can directly copy-paste cards from these briefs into your files without needing to cut the card yourself.

For reference, Google Docs are not exact equivalent to the preferred Verbatim Word Docs format, but Google Docs is a somewhat close substitute.

PDF briefs also usually have a table of contents on the top of the file., showing the page numbers for each argument. Several from Champion Briefs and VBI are shown above.

When using PDF briefs, navigating back and forth between the individual cards and the table of contents can be annoying, as you cannot see the table of contents simultaneously with cards like you can with MS Word/Google Docs. Instead, you must scroll back and forth between the "meat" of the brief and the table of contents on the top (or have the table of contents open on another tab/monitor).

Some briefs have an in-built sidebar table of contents in PDF viewers. This avoids most of the issues related to needing to scrolling up and down to find page numbers in the table of contents. Some briefs offer this feature, such as VBI, while others do not, like Champion Briefs or Kankee Briefs.

Word Docx briefs often exclude a table of contents because Word has an in-built nav pane sidebar on the left. The nav pane makes a table of contents in the document itself redundant. This also better integrates the Verbatim header hierarchy, where "pockets" > "hats" > "blocks" > "tags."

A similar feature exists in Google Docs called the document tabs. Pictures of the Verbatim sidebar and the Google Docs sidebar are shown below.

Some briefs, such as VBI and Kankee Briefs, have numeric codes representing what subsection of the brief you are looking at. For instance, the below VBI card is 6..5.4, meaning it is section 6 (aff evidence), subsection 5 (AT: R&D), card 4. You can also see this in the sidebar in terms of aff is the overarching header, with AT: R&D the fifth subsection, and "AT: 1 in 5,000 Success Rate" being the fourth card.

Kankee Briefs does something similar for the topic analysis. For instance, the label 1.3.1 indicates we are in the first section (topic analysis), third subsection (neg), and first contention explanation.

I know this is somewhat technical, but the essentials are that (a) PDFs briefs are plain-text cards that you need to cut yourself, and the tables of contents are somewhat wonky, and (b) Word Docx briefs are pre-cut cards designed for use in Verbatim/MS Word or Google Docs, and your "table of contents" is your nav pane on the left. You do not need to understand all the nuances of how briefs function as you presumably are not writing briefs; you only need to know enough for you to have a good time reading a brief and not be lost in several hundred page documents without navigation tools.

Content of Briefs

Topic Analysis

The topic analysis is the overarching narrative of the arguments within a debate brief, where the brief author explains the fundamentals of the topic alongside some strategic interactions and general arguments that could be read on the topic. This does not necessarily need to be directly related to the content of the brief itself; many topic analyses are general takes on the topic and do not discuss the intricacies of the contentions in the brief itself. This means that even if you don't plan on using any cards from a brief, it is still worthwhile for you to read their topic analysis as it is a primer/jumping off point for topic research.

Remember that for many briefs, their topic analysis is actually topic analyses, where ~4 coaches write their own, disparate topic analyses that are all included in the final brief. You get a variety of viewpoints, but to some degree there is some degree of repetition as different coaches will sometimes have similar explanations of the topic, especially in terms of topic background.

In contrast, some topic analyses are excessively long, and take up a similar amount of space as 4 distinct topic analyses. In my case with Kankee Briefs, that is because I wish for you to have a good understanding of the topic, and more particularly, how these arguments in the brief function. To my knowledge, Kankee Briefs and Champion Briefs offer specific, targeted explanations of the substance of each contention (though we present them in different places throughout the brief, as seen in the brief format section above).

Contentions and Blocks

After the topic analysis comes the contentions. These include some generic, mainstream contentions as well as some more fringe contentions that are often oriented towards circuit debate.

Often intermingled in the "meat" of the brief are blocks to answer the arguments presented elsewhere in that brief. This is the case for VBI and Champion Briefs. Kankee Briefs instead releases a separate AT File a week after topic debates begin in order to have case-specific answers based on what arguments were presented on the LD Wiki.

Similarly, many cases have built-in answers to core aff/neg arguments, which will be presented in the contention itself. For instance, on the 2021 Sept-Oct topic on medical intellectual property rights, Kankee Briefs presented a patent trolling contention, which link turned the innovation DA. However, even if you didn't read that contention as offense in the 1AC because of the fact you read other contentions, you could still read those link turns in the 1AR to answer the innovation DA. As neg, you similarly can read links from other disadvantages as link turns on case.

If you're using other briefs, you need to cut blocks yourself, as the other briefs usually ONLY have contentions. However, as explained below, you should ALWAYS cut your own cards on a topic, and not treat a brief as a substitute for original research.

You ought to peruse whatever briefs you have access to, first in order to find potential cards to utilize for your own cases or block files, and second, and more importantly, to scout what other people are reading on the topic.

Argument Trackers

Whenever a new topic comes along, you need to be using an argument tracker to make an on-going list of each and every argument you need to answer in your block file. This also gives you a good idea of what the core generics are on the topic, and you can design winning 1NCs based on the predicted 1AC (and vice versa).

Whenever you see an argument, or even think of a potential argument that could, in some hypothetical world, possibly be an argument that someone (even if that person is very bad at debate) could read, write that argument down in your argument tracker. That is now an argument you NEED to have a pre-written response to, ideally with at least 1 card. Briefs and the LD Wiki are great sources for scouting, and you should use them as a list of every possible argument you could hit at a tournament.

To effectively use an argument tracker for brief argument scouting, please read our article entirely focused on explaining the article tracker in detail (linked here). The file is from

Set yourself up for success with a good philosophy behind debate prep. If you want to reach higher echelons of debate, not knowing about an argument, or worse, knowing about it and not doing anything to prep it out, is not an excuse. If, while reviewing brief files, you learned that VBI produced a Ripstein NC, and you didn’t prep out that argument thinking you’ll never hit it, losing to that argument is your fault. In almost every circumstance in which you lose to an unfamiliar argument, that loss was preventable. You should have been more prepared, and if you're forgetting to prep out arguments due to forgetting that they exist, that loss is your fault.

In low level and lay debate, being a marginally better debater means you can skate by when hitting unfamiliar arguments, as the skill differential between you and your opponent is likely fairly big. In contrast, if you want to win the most prestigious high school debate tournament, the TOC, you cannot hedge your bets on your opponent being so sufficiently bad as to filter out the impact of you not being prepared for new/fringe arguments. Competing against the best of the best means, by definition, there’s a much greater chance your opponents will be at your level, or worse, better than you, and both types of opponents are structurally incentivized to read new/fringe arguments to get a marginal competitive advantage against you.

With every new topic, you'll review a great deal of articles, speech documents, and briefs. All of this is decentralized and hard to keep track of in your head. We've invented written language for the explicit reason of allowing you to "think with your keyboard," and write down what you need to answer. The onus and personal responsibility is on you to be prepared to win a round against that argument, as these are ALL potential arguments you could hit on the circuit, however unlikely you are to hit them.

Similarly, make a topic notes document for you to jot down whatever important info you've learned about the topic from whatever number of topic analyses your read and whatever topic research you do. For instance, on the current plea bargaining topic, if you learned that El Paso or Alaska are examples of attempted plea bargaining abolition, those are great areas for future case study research. Learning why the US have plea bargaining unlike many other countries is a jumping off point to research why we can or cannot be like other countries. Having a mini-history explanation at the ready in your notes is crucial context for questions related to how the process evolved: was it gradual and unregulated, or was it a sudden change under a new policy. The answer is highly relevant to discussions of whether plea bargaining is coercion or not.

Tips and Advice on Using Briefs

Briefs Are a Complement, not a Substitute, for Original Research

Ultimately, whenever a debate company provides you with briefs, they're intending that you to use their evidence as a supplement, not a replacement, for your own research. If a coach produces a brief, this is either as a means of advertising for their camp (one of the main reasons institutions make briefs), or they want to assist you and your research.

They (hopefully) already know how to research, so their doing the entirety of the research for you and you merely reading what they wrote verbatim is a bad practice. It means your understanding of the argument is worse, you're now reliant on other people to do your work, and you're not developing research skills, one of the key benefits of the activity. "Docbot" debaters who merely read off a speech document someone else wrote, with little contribution to the block files nor understanding of the arguments, may win some rounds, mostly due to the fact that their coaches probably can cut better cards then most high school debaters, but there's an upper limit on how far you can go. If you are 100% reliant on briefs or LD Wiki dredging/mining for your cards up to a varsity level, you are missing crucial time for skill development, and you will be structurally behind compared to other debaters who spent their novice/JV seasons researching on your own. Except for high-level out-rounds, winning is not necessarily the best metric of skill when that win can be the result of skillful people assisting that debater.

All mainline brief organizations openly state that our briefs should not be a one-stop shop for all your card needs. You need to research on your own; otherwise you will do well at the beginning of your debate career and slowly taper off as you face increasingly more skilled opponents.

Remember while browsing briefs that many cases' contentions are built-in answers to core aff/neg arguments, so even if you are not interested in running that contention, it may still be worthwhile to read that contention for potential block file AT cards.

Check Brief Evidence

Under NSDA Evidence Standards, you are obliged to check all the evidence in each brief to ensure that the brief's cards match the source text, as ultimately you are responsible for and will be punished in-round for any evidence violation. If this sounds unreasonable for you to check several hundred pages of cards to ensure they matchup with the original source, that is fair, but rules are rules.

If you do not believe me and need evidence about that rule, I put quotes from page 37 and page 186 of the handbook below for reference.

Debaters, even if they have acquired the evidence other than by original research, are responsible for the content and accuracy of all evidence they present and/or read.

Question: A team/individual reads evidence in a round that comes from a) a purchased handbook, b) the Open Evidence Project sponsored by the NDCA, or c) a debate institute evidence packet. The other team calls for the original source of their evidence. The team/individual a) shows the original page from the handbook, b) shows either the original electronic or printed version of the OEP download or shows the web page from which the evidence was procured, or c) shows the electronic or printed version of the institute evidence. Is this sufficient proof for the original source? Answer: Yes. The team/individual has met the burden of demonstrating the original source of the evidence. However, if the team/individual uses any of these sources, they are still responsible for the validity of the evidence.

I will admit that I have made mistakes in the process of making briefs over the years, and have updated the relevant files with corrections. I do not know how other brief organizations deal with this issue, but what I can guarantee you is that inevitably, someone, somewhere, in some brief organization or another will, unintentionally, produce bad evidence at some point, and that won't be caught by the brief organization.

This is unfortunate, and I hope it happens comparatively less to Kankee Briefs then other brief organizations, but it happens. Anyone who says otherwise and says they've checked every jot and tittle of every card in a 600+ page file is either lying to you or lying to themselves. And this is why you ought to safeguard yourself from losing a round due to not checking your evidence, as the NSDA Evidence rules say its your problem (even know we and other debate organizations cut the cards).

Modify Cards for Language as Needed

A common argument in circuit debate is the Word PIK, where the other side kritiks your use of non-inclusive language. This often is related to gendered language, such as he, his, hers, etc., in place of gender-neutral language for generics that don't refer to anyone in particular. Of course, don't misgender figures you know to be a specific gender by changing their gendered pronouns to be gender neutral, like saying Pablo Escobar is non-binary in a cartel advantage, and do be considerate of how gendered language works in other countries (i.e., Latin Americans think that the term Latinx is a colonial tragedy against language).

The second most common issue with non-inclusive language is verb analogies about disabilities, such as handicap, crutch, cripple, etc., particularly those being used in non-medical contexts.

An example of a kritik of language can be found on the 2026 Jan-Feb nuclear weapons topic, where Kankee Briefs has a kritik of potentially dis/ableist language from the anti-nuclear weapons community (see page 70 linked here). The more an aff demonizes disabled people to advocate against nuclear weapons via their language, the more the aff would link to the kritik. However, people can argue against nuclear weapons without tropes of "insanity," "madness," and "nutcases," which can be done via card modification

If you want to avoid the Word PIK, find all non-inclusive language in your highlighted text. Strikethrough that word (a Word Docx explanation is linked here) and add a replacement word in brackets that is a more inclusive term. This would usually be a gender neutral term or a generic verb that is not a disability metaphor. Do not delete the original word; we strikethrough it to indicate that was in the original text, and we have modified it for language. Then, add a note below the citation indicating the change, such as "*NOTE: modified for language."

Even if you disagree with the nuances of how we ought to treat gendered/disability language, which is an argument you can have, this is not an argument you need to have. If you don't change the language of your cards, at least in circuit debate rounds, you have needlessly added a kritikal/theoretical reason to vote you down, no matter how high quality the substance of your post-fiat arguments are.

Conclusion

Based on all this, you should have a good grasp of how to use briefs and what briefs to buy/use. This means you should now understand them at the most fundamental level, and all least begin to think critically on how to best use briefs to your advantage (even if you don't plan on using any brief arguments).

If you have any corrections regarding the info about other briefs or have a question about best brief usage practices, please email me at karkingkankee@gmail.com